Muddling Towards Golden Gate

By Michael Petrie

They say you never forget your first time. For me, cruising offshore began onboard Azulo, a 20-year-old, 31-foot Mariner ketch. Three friends—Dave, Karl, and Allen—and I set out to follow the path of 19th-century writer Richard Henry Dana, up the California coast. A motley crew of four young sailors off sailing the high seas!

I kept a journal during that first cruise, and I still have it today. “Until now,” I wrote, “my longest time at sea was a 10-hour sail from Oxnard to Catalina Island. I’ve been longing for a taste of real cruising and decided my first time should be a leisurely port-to-port crawl from Marina del Rey to San Francisco.”

The first leg, to Santa Barbara, was a pleasant motorsail with the Channel Islands to our left and the rugged California coast to our right. But from Santa Barbara northward, the going became substantially more challenging.

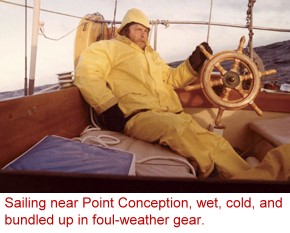

We left Santa Barbara at dawn and sailed north toward Point Conception, which has been called the “Cape Horn of the Pacific” because of the heavy northwesterly gales frequently encountered there. If Point Conception was true to form, I’d soon be getting my first taste of heavy-weather sailing.

By 1900 we were definitely in the vicinity of Point Conception. The wind was over 35 knots, and the seas were growing. I crept cautiously out onto the bowsprit to furl the jib, perched over the bow like a figurehead as the boat plowed through the waves. One swell lifted me up, up, up to such a height that it seemed we were pivoting precariously on the boat’s transom like the fishing boat in the movie The Perfect Storm just before those onboard met their doom; another foot and the boat would certainly topple over backward, or so it felt.

The wave suspended me there for a moment, dangling in mid-air and clutching the bowsprit. All at once the boat came free-falling through the air with a crash. I was engulfed by water as the bowsprit stabbed into the ocean like a dart on a dartboard. Without my harness, I would surely have been pitched headlong into the turbulent seas. And this was only the beginning of our bout with Point Conception.

Dave took the helm, and I went below to get as much sleep as possible since it would take all night to round the point. That was a frightening experience. I’d never been seasick, but I felt the first pangs as I made my way around the cabin. Lying down with my eyes closed felt like being on a bad drunk with bed spins.

To take my mind off the bouncing world in which I was entombed, I thought about my girlfriend back home. As I entered that never-never land somewhere between consciousness and unconsciousness, I swore I could detect the sweet smell of her hair. I could see her face. I could hear her angelic voice speaking to me: “Mike.” First it came softly, like part of a fog-filled dream, then sharply: “Mike!” It was Karl shouting my name from the cockpit.

Karl was at the helm, cold and wet and more than ready for me to relieve him. Had I really been asleep for six hours? I sat up and was immediately thrown out of the bunk, crashing into the galley table with an awful thud. The noise awakened Dave, who mumbled, “Hey man, are you all right?” I assured him I was, though I wasn’t sure it was true.

I stumbled around in the dark cabin, doing a sort of dance while trying to pull on my boots and foul-weather gear, when I suddenly realized I was stepping on Allen, who had passed out on the floor in a seasick stupor. Sidestepping him, I climbed out the companionway, hitting my head on the sliding hatch, and got myself to the wheel. We had only the storm jib up and the engine was on.

On deck alone in the black of a moonless night, I felt the boat pitch and plunge. She’d heel far over and waves would crash on us, filling the cockpit nearly to my knees. Salt spray burned my eyes so at times I couldn’t see anything at all. And if I looked away from the compass for only a second, we’d bounce and leap off course, 30 to 40 degrees in a single bound. At one point I found myself heading almost due north instead of due west, then a moment later we’d jump back to the proper heading.

It was tiring and very, very cold. My hands felt as though they were frozen to the wheel, my feet were numb, my cheeks and chin were raw from the wind. I was nauseated by the violent motion of the boat, and I was absolutely loving it! Fulfilling my dream of ocean cruising and learning, first hand, about sailing in heavy weather, I couldn’t have been more thrilled.

As morning came, the fog was so thick that the only evidence of dawn was the gradual lessening of darkness. Veiled daylight was preferable, though, to rockin’ and rollin’ in total darkness. At 0630 I woke Dave for his watch. Relieved, I took off my wet clothes and dove below into a damp sleeping bag. I didn’t open my eyes again for three hours, when we were approaching Port San Luis, a welcome patch of tranquillity where we dropped the hook and spent the rest of the day drying out.

We zoomed into Morro Bay the next day, swept along by the 5-knot current that flows down the channel, and grabbed a mooring. We departed the following morning just as the sun began to rise. Lots of stars and a full moon were still visible in the sky, as were several large sharks in the channel. It was creepy observing those dorsal fins and tails slicing the glassy surface of the water. Yet by noon I was sitting out on the bowsprit, watching more-comforting dolphins swimming and frolicking beneath me.

With Point Sur nearly abeam, we headed almost due north with the reefs shaken out, just screaming along, burying the rail. I was enjoying myself, as if racing some invisible competitor. Heeled over, the wind and spray in our faces…this is what sailing is all about!

As nighttime darkness fell and shipmates went below to rest, I couldn’t help but appreciate how wonderful it was to be alone in the cockpit, the only sound made by the sea against the hull, the moon casting its shadow on the sea. Several hours later, however, that sense of peace gave way to concern that bordered on fear. Just goes to show, you shouldn’t get complacent when you’re out at sea. I noticed something dangling free on the leeward side, revealed by closer inspection to be a lower main shroud. Uh oh! I lashed the dangling shroud to a lifeline and continued on, hoping for the best.

Then, at around 0430, I got lost. I knew that, on our present course, we should be approaching Santa Cruz and I should be seeing land soon. I scanned the horizon in every direction for a light on shore, but saw nothing. By 0500 it was no longer dark, and we were engulfed in a heavy gray fog. The wind and seas had calmed considerably, but in the limited visibility I saw no sign of land.

My concern was increasing; we could be washed ashore if we weren’t careful. Finally, Dave popped his head up through the hatch and asked if I’d seen any lights. I told him that I hadn’t. In short order, he was searching from the foredeck as I stayed at the wheel. Just as he’d dropped the mainsail and I’d started the engine, I spotted a light. “Gawd! Turn around…reverse heading!” Dave shouted. I could tell from the panic in his voice that I’d better be damned quick about it.

With the course change we were now headed due south—exactly the wrong direction. Eventually the fog burned off in the morning sun and we got ourselves back on course, but it was a pretty hairy way to start the day—a day that ended with us anchored for the night at a beautiful and serene spot called Half Moon Bay, where we repaired the rigging.

Not long after leaving Half Moon Bay, we spotted one of the towers of the Golden Gate Bridge. I think it was Allan who saw it first. His face just beamed; he was really excited. Our arrival at San Francisco Bay was, it seemed to us, nothing short of spectacular. Karl proclaimed that sailing into San Francisco is the grandest way to arrive, and the rest of us heartily agreed.

Our little blue-and-white boat, on a deep blue ocean and under a cloudless blue sky, was the only vessel around. We entered the waters of the bay as if we owned it, sailing under the Golden Gate Bridge with sails full and proud. The surrounding green hillsides were beautiful, and we could smell the land. All four of us, I think, viewed the bridge as a sort of finish line for our northward passage. Despite our foibles and outright blunders along the way, we had arrived.

“My first foray into ocean cruising has barely whet my appetite,” I wrote. “My clothes are still wet, and dreams of sailing to Hawaii are already forming.”

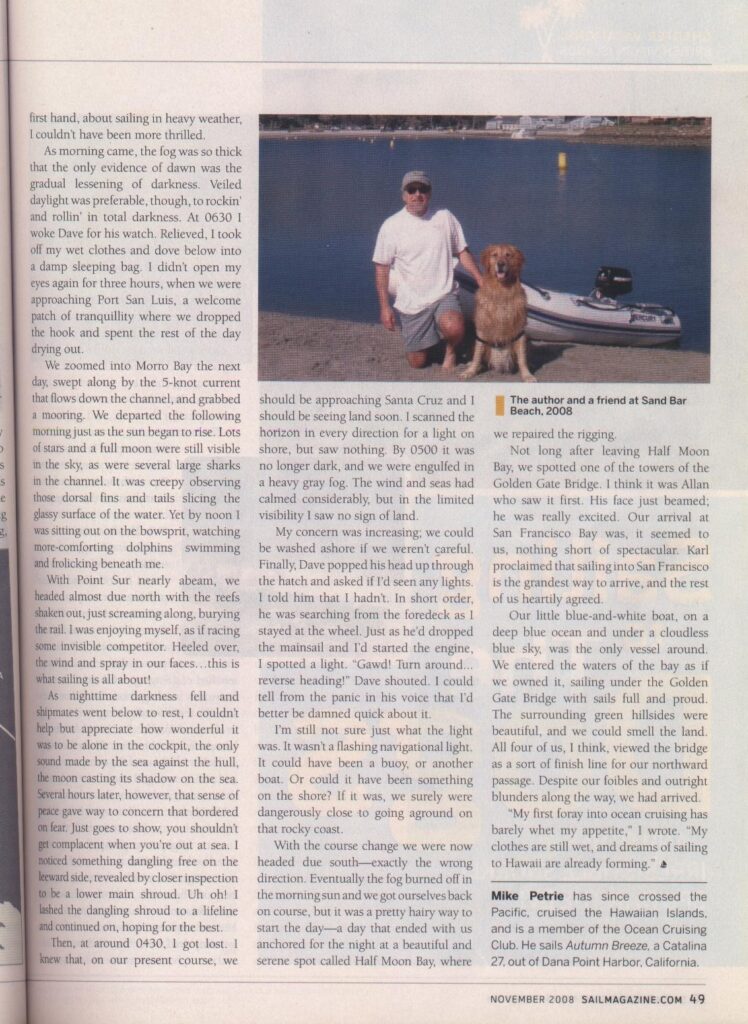

Mike Petrie has since crossed the Pacific, cruised the Hawaiian Islands, and explored much of the South Pacific, including Tonga, Samoa and Tahiti. He is a member of the exclusive Ocean Cruising Club which prerequisites members to have completed a minimum of a 1000 mile ocean crossing between landfalls. Currently he sails Autumn Breeze, a Catalina 30, out of Dana Point Harbor, California.